Table of contents

- Acknowledgements

- Executive summary

- Objectives, intended users and context of this report

- Outline of this report

- Methodological approach

- Lessons learned from collaborating with member countries through the self-assessment survey

- 1. Rationale for public intervention on adaptation

- 2.1. Key Topic 1: Public and policy awareness of the need for adaptation

- 2.1.1. Awareness of the need for adaptation: what does this include?

- 2.1.2. Findings from self-assessment survey

- 2.1.3. Examples from countries

- 2.1.4. Discussion of findings

- 2.2. Key Topic 2: Knowledge generation and use

- 2.2.1. Knowledge generation and use: what does this include?

- 2.2.2. Findings from self-assessment survey

- 2.2.3. Examples from countries

- 2.2.4. Discussion of findings

- 2.3. Key Topic 3: Planning adaptation

- 2.3.1. Planning adaptation: what does this include?

- 2.3.2. Findings from self-assessment survey

- 2.3.3. Examples from countries

- 2.3.4. Discussion of findings

- 2.4. Key Topic 4: Coordination of adaptation

- 2.4.1. Coordination of adaptation: what does this include?

- 2.4.2. Findings from self-assessment survey

- 2.4.3. Examples from countries

- 2.4.4. Discussion of findings

- 2.5. Key Topic 5: Stakeholder involvement

- 2.5.1. Stakeholder involvement: what does this include?

- 2.5.2. Findings from self-assessment survey

- 2.5.3. Examples from countries

- 2.5.4. Discussion of findings

- 2.6. Key Topic 6: Implementation of adaptation

- 2.6.1. Implementation of adaptation: what does this include?

- 2.6.2. Findings from self-assessment survey

- 2.6.3. Examples from countries

- 2.6.4. Discussion of findings

- 2.7. Key Topic 7: Transnational cooperation

- 2.7.1. Transnational cooperation: what does this include?

- 2.7.2. Findings from self-assessment survey

- 2.7.3. Examples from countries

- 2.7.4. Discussion of findings

- 2.8. Key Topic 8: Monitoring, reporting and evaluation

- 2.8.1. Monitoring, reporting and evaluation (MRE): what does this include?

- 2.8.2. Findings from the self-assessment survey

- 2.8.3. Examples from countries

- 2.8.4. Discussion of findings

- 3. The evolving agenda for national adaptation in Europe

- 4. Glossary

- 5. Acronyms

- 6. References

2.1.4. Discussion of findings

The role of extreme events: Enhancing awareness of the need for adaptation and triggering adaptation

As summarised in Figure 2.1, common triggers for action on adaptation selected by reporting countries were extreme weather events, damage costs, EU policies and scientific research. Given the nature of the climate change adaptation issue, extreme events have played a particularly significant role in defining adaptation as a problem (Keskitalo et al., 2012). Climate-related events such as floods and droughts, as well as events such as the 2003 European heat wave, have played a significant role in pushing the adaptation agenda forward. While drawing attention to the weather events themselves, these events have been increasingly linked to climate change and socio-economic developments (EEA, 2013). These events, along with statements linking extremes to anthropogenic climate change from the scientific community such as the IPCC SREX and IPCC AR5 (IPCC 2012; IPCC WGI, 2013; IPCC WGII, 2014) have raised the awareness of the need for action on climate change and that this action needs to include adaptation.

Policy (political awareness of the need for adaptation) has been enhanced by these extreme events and the resulting concerns related to avoiding the high future costs such as those identified in the Stern Report (2006). These events can provide windows of opportunity during which policy and programmes can be introduced as the support for a responsive policy intervention is increased based on the perceived associated benefits and costs. Keskitalo et al., 2012 showed the benefits to the policy agendas at the national and local levels when, as a result of concerns often triggered by observations and an increased understanding of the implications and science, there is a strongly integrated, multi-participant group united in their calls for action.

At the national and sub-national (provincial, regional and local) levels, the social, economic, and environmental costs of these extreme events are reported by media; impacting on national and sub-national budgets. As such, these extreme events increase public awareness of the need and public demand for action with consequences for political awareness. The fact that many governments at both national and sub-national levels are particularly focused on economic (and social) growth and development (and jobs), political awareness of the need for action is enhanced as these extreme events can have significant negative implications relative to meeting desired outcomes. Political awareness is also enhanced by the increased recognition that taking such actions, including adaptation, can also positively impact on economic (and social) growth and development and provide jobs.

Enhancing awareness of the need for adaptation requires information that recognises the diversity of the audiences and that is consistent with an environment for open-minded, unbiased consideration of the best available scientific information

Concerns have recently been raised that although levels of concern and awareness about, and the scientific basis for, climate change have been increasing over the past 20 years, progress on mitigation and adaptation is far less than would be expected (Pidgeon, 2012). Possible explanations cited are issues of fatigue, the impact of the global financial crisis, distrust and the influence of climate sceptics, and the deepening politicisation of climate change. Pidgeon (2012) also noted that other global/ societal, environmental or personal issues occupy the ‘finite pool of worry’ and what matters most in citizen engagement is the expressed ‘issue importance’ (Nisbet and Myers, 2007), rather than their basic levels of expressed concern.

Social science theory and much empirical research show that links between information and behaviour can be tenuous at best (Chess and Johnson, 2013). Information is not entirely inconsequential, but it is overrated as the prime driver for change.

Traditional approaches when supplying information to support action often include a focus on simplifying the information, including avoiding overly technical language, providing more information and using ‘trusted’ communication channels and parties. Best practices, however, also recognise the diversity of audiences, the need for dialogue rather than just supplying information, the need to provide information about the harmful outcomes along with actions to avoid or reduce those impacts, and the evaluation of communication impacts (Chess and Johnson, 2013).

People’s grasp of scientific debates such as climate change, can improve if the information they receive builds on the fact that cultural values influence what and whom they believe (Kahan, 2010). This suggests that enhancing visibility with the aim of stimulating action requires a move beyond just providing more information on climate change and adaptation information and going beyond the traditional conception of risk communication such that what is provided is more closely aligned to the cognitive and emotional needs of both policy makers and the public. In so doing this would lead to creating an environment for open-minded, unbiased consideration of the best available scientific information.

Understanding the role of awareness of the need for adaptation requires further work

The analysis of the responses to the self-assessment survey reconfirms that adaptation can be motivated by a number of factors, of which awareness of the need for adaptation can contribute, even in the broadest sense. Our understanding of the role of this awareness as a contributing factor is in part compounded by the complex nature of adaptation. For the most part adaptation actions are not isolated from other decisions, policy and activities and they are developed, delivered and evaluated in a specific context (e.g., socio-economic, cultural, and political) at the local, regional, national or multi-national scale, but are also influenced by international factors (e.g., financial markets, international politics and trade).

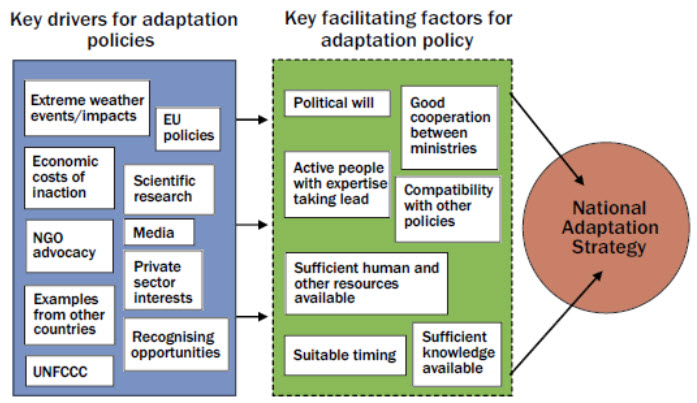

There are also a number of triggers for adaptation and, as suggested in the above analysis of the self-assessment survey responses, many of these can play a role in enhancing public and political awareness of the need for adaptation. They are in themselves also reflective of the complex nature of adaptation. Figure 2.6 taken from the PEER report (Swart et al., 2009) provides an illustration of key drivers and facilitating factors.

Figure 2.6 Key drivers and facilitating factors for national adaptation strategy (Swart et. al 2009)

Similar to the PEER report, in responding to the self-assessment survey, extreme weather events, together with estimates of current and future damage costs, development of EU policies and pertinent results from scientific research were commonly selected influences for triggering adaptation. In the context of awareness of the need for adaptation, these identified triggers can lead to an increase in public awareness of the need for adaptation and can also raise adaptation on the political agenda (as a political response to the trigger, including as a response to public demand).

The complexity of the role of these drivers/triggers is reflected in the responses to other questions related to adaptation at the national level (Table 2.4). For those 24 countries that agreed or strongly agreed that the need for adaptation has reached the national political agenda, selected triggers are extreme weather events (selected by 22 countries), damage costs (selected by 14 countries), EU policies (selected by 14 countries), and scientific research (selected by 12 countries).

For those 26 countries that reported a medium, high or very high willingness to develop policies and to take adaptation actions at the national level, important triggers for adaptation selected were the same – extreme weather events (selected by all but one), EU policies (selected by 16 countries), damage costs (selected by 14 countries) and scientific research (selected by 14 countries). The selected drivers suggest that an important trigger for adaptation is responding to extreme weather events and damage costs, and in response to EU policies. Scientific research is an important trigger, but selected less often than those previously mentioned.

The complexity and effectiveness of these triggers for adaptation becomes apparent when looking at the responses of those countries that reported a low willingness to develop policies and to take adaptation actions at the national level or reported that they neither agreed or disagreed that need for adaptation has reached the national political agenda (Table 2.4).

Table 2.4 Selected triggers for adaptation and responses to questions related to adaptation at the national level

| Triggers for Adaptation | Willingness to develop policies and to take adaptation actions | Need for adaptation has reached the national political agenda | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | Medium | High/Very High | Neutral | Agree / Strongly Agree | |

| Extreme weather events | 3 | 13 | 12 | 4 | 23 |

| UNFCCC process | 0 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| EU policies | 2 | 10 | 7 | 4 | 15 |

| Damage costs | 3 | 9 | 5 | 2 | 14 |

| Forerunner sectors | 0 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 4 |

| Adaptation in neighbouring countries | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Scientific research | 0 | 8 | 6 | 2 | 12 |

| Media coverage | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

The selected triggers are similar in both cases suggest that understanding the nature and effectiveness of what triggers adaptation is complex and that further efforts to identify the specific nature of the factors motivating adaptation and to analyse these drivers/triggers and the specific circumstances is warranted.

Another point requiring further investigation is whether or not ‘sufficient knowledge available’ is a key facilitating factor for adaptation policy. The responses to the self-assessment survey considered under this topic suggest that although necessary, there is a need to move beyond attributing the lack of adaptation action solely to amount of knowledge (and information) available to considering what aspects of that knowledge (and information) triggers the required actions. Although somewhat more difficult to identify, the potential benefits would suggest that understanding this aspect of knowledge and information as a trigger for adaptation would be worthwhile.