Table of contents

- Acknowledgements

- Executive summary

- Objectives, intended users and context of this report

- Outline of this report

- Methodological approach

- Lessons learned from collaborating with member countries through the self-assessment survey

- 1. Rationale for public intervention on adaptation

- 2.1. Key Topic 1: Public and policy awareness of the need for adaptation

- 2.1.1. Awareness of the need for adaptation: what does this include?

- 2.1.2. Findings from self-assessment survey

- 2.1.3. Examples from countries

- 2.1.4. Discussion of findings

- 2.2. Key Topic 2: Knowledge generation and use

- 2.2.1. Knowledge generation and use: what does this include?

- 2.2.2. Findings from self-assessment survey

- 2.2.3. Examples from countries

- 2.2.4. Discussion of findings

- 2.3. Key Topic 3: Planning adaptation

- 2.3.1. Planning adaptation: what does this include?

- 2.3.2. Findings from self-assessment survey

- 2.3.3. Examples from countries

- 2.3.4. Discussion of findings

- 2.4. Key Topic 4: Coordination of adaptation

- 2.4.1. Coordination of adaptation: what does this include?

- 2.4.2. Findings from self-assessment survey

- 2.4.3. Examples from countries

- 2.4.4. Discussion of findings

- 2.5. Key Topic 5: Stakeholder involvement

- 2.5.1. Stakeholder involvement: what does this include?

- 2.5.2. Findings from self-assessment survey

- 2.5.3. Examples from countries

- 2.5.4. Discussion of findings

- 2.6. Key Topic 6: Implementation of adaptation

- 2.6.1. Implementation of adaptation: what does this include?

- 2.6.2. Findings from self-assessment survey

- 2.6.3. Examples from countries

- 2.6.4. Discussion of findings

- 2.7. Key Topic 7: Transnational cooperation

- 2.7.1. Transnational cooperation: what does this include?

- 2.7.2. Findings from self-assessment survey

- 2.7.3. Examples from countries

- 2.7.4. Discussion of findings

- 2.8. Key Topic 8: Monitoring, reporting and evaluation

- 2.8.1. Monitoring, reporting and evaluation (MRE): what does this include?

- 2.8.2. Findings from the self-assessment survey

- 2.8.3. Examples from countries

- 2.8.4. Discussion of findings

- 3. The evolving agenda for national adaptation in Europe

- 4. Glossary

- 5. Acronyms

- 6. References

1. Rationale for public intervention on adaptation

KEY MESSAGES

- Public authorities play a critical role in adaptation action. They are in a unique position to identify and address current and future risks and opportunities.

- Public-sector interventions should complement and support adaptation activities taken by the market and private actors.

- In the last ten years, many policy frameworks have been developed to help improve the capacity of societies and economies to adapt.

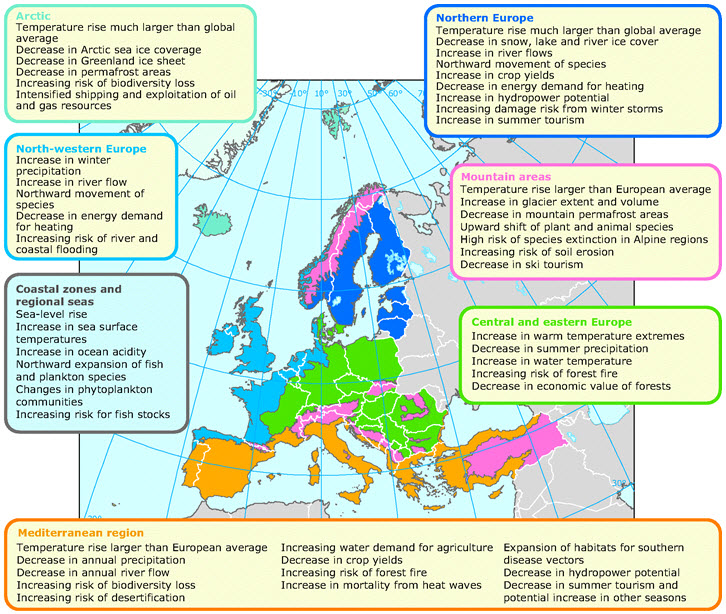

Significant changes in climate and its impacts are already visible in Europe today. Increasing temperatures, rising sea level, melting of glaciers and ice sheets as well as more intense and frequent extreme weather events are among the challenges already driven by climate change. IPCC AR5 (IPCC WGII, 2014) confirms key risks to increase for Europe with climate change projected to have adverse impacts in nearly all sectors and across all sub-regions, although with large differences in impact types. Regional variations have been shown by EEA 2012 mapping the observed and projected climate change and impacts for the main biogeographical regions in Europe (Figure 1.1). Further climate change impacts are projected for the future which can increase existing vulnerabilities and deepen socio-economic imbalances in Europe (EEA, 2012). However, adaptation prospects exist that have the potential to lower projected risks.

Figure 1.1. Observed and projected climate change and impacts for the main biogeographical regions in Europe (EEA, 2012)

Impacts of climate change that are already observed, in particular damages and related direct and indirect costs caused by extreme weather events are often the initial driver for public authorities to act on adaptation. Adaptation involves reducing risk and vulnerability, seeking opportunities and building the capacity of human and natural systems to cope with climate impacts, as well as mobilizing that capacity by implementing decisions and actions (Tompkins et al., 2010). Over the last decade, significant progress has been made in ways to respond with adapting to climate change, in particular with regard to policy development. This progress responds to the growing awareness that it is necessary to deliberately plan adaptation, which proactively addresses potential risks and opportunities and takes into account the wider socio-economic dimensions.

Besides the clear recognition that conditions have changed or are about to change, past and current efforts in developing and implementing adaptation polices are also driven by the fact that autonomous action by economies and societies is expected to still be insufficient to address the complexity, range and magnitude of risks associated with climate change and socio-economic developments. Public intervention can thus be considered as a strategic and collaborative effort in coping with existing and future climate risks and exploiting opportunities. This is in particular relevant for an interdisciplinary arena like climate change adaptation where a multitude of actors need to join forces for concerted action. Governments therefore hold an important role to support society by intervening with a mix of policies and action for certain negative effects and opportunities of climate change that cannot be addressed by private actors and market forces alone. Public authorities (national, regional, local) are thus challenged with building the policy competence to take up this responsibility under the condition that any public intervention should be a complement to the market and individual activities and not replace or duplicate them (Edquist and Chaminade, 2006).

The approaches for adaptation planning are also driven by the aim to take decisions that remain both robust (to cover all plausible climate change scenarios) and flexible (so the measures can be changed if conditions change) to cope with an uncertain future (Schauser et al. in Prutsch et al., 2014). In this regard results from scientific research can additionally highlight areas where public intervention is needed or needs to be adjusted and thus inform decision making with evidence.

Public intervention on adaptation is therefore framed around the general objectives to avoid adverse effects of climate change on the environment, society, and the economy and to take advantage of potential opportunities, as well as building adaptive capacity to address the associated challenges. This includes supporting a productive, healthy and resilient society that is well-informed and prepared for the challenges and opportunities associated with a changing climate. More specifically, a mix of policies and action shall foster well-targeted and concerted adaptation initiatives that enable and stimulate individual actors to proactively cope with changing conditions.

There is an array of instruments which can be made operational for public intervention on adaptation, either separately or as part of an adaptation policy. These include initiatives to build adaptive capacity, enhance knowledge generation and dissemination, facilitate mainstreaming, set new or amend existing regulations and standards, provide financial support (incentives, subsidies, taxes), make use of insurance schemes. The use of various policy instruments should be geared towards being complementary and supportive of adaptation activities taken by all stakeholders, including the private actors. The choice of suitable intervention options will depend on various conditions, such as the political system of a country, coordination and consultation mechanisms, existing instruments relevant for adaptation, etc. In addition the heterogeneity in adaptation planning is related to the context specific nature of adaptation (differences in resources, values, needs, and perceptions among and within societies) that governments need to take into account (IPCC, 2014). Thus approaches for public intervention vary reflecting different governance and societal systems and policy making practices.

Despite the heterogeneity in intervention approaches, significant advancements have been made in establishing policy frameworks at different levels of governance that share the overarching intention to support societies to adapt.

At the international level the community under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) agreed that adaptation is imperative as a complementary second column of climate policy (to mitigation). European countries and the European Commission being Parties to the Convention have committed themselves to “formulate, implement, publish and regularly update national and, where appropriate, regional programmes […] and measures to facilitate adequate adaptation to climate change” (Article 4, paragraph 1 of the UNFCCC Convention). This commitment has been refined under the Cancun Adaptation Framework (CAF) with Decision 5/CP.17 on National Adaptation Plans1. Herewith the Conference of Parties acknowledged “that national adaptation planning can enable all developing and developed country Parties to assess their vulnerabilities, to mainstream climate change risks and to address adaptation”.

In the view that planning for adaptation requires a strategic approach at European level, the European Commission has prepared an adaptation framework for Europe to ensure timely, efficient and effective adaptation actions coherently across sectors and levels of governance. EEA 2013 highlighted five main reasons for the EU to take action on climate change adaptation:

- Many climate change impacts and adaptation measures have cross-border dimensions;

- Climate change and adaptation affect EU policies;

- Solidarity mechanisms between European countries and regions might need to be strengthened because of climate change vulnerabilities and adaptation needs;

- EU programmes could complement Member State resources for adaptation;

- Economies of scale can be significant for research, information and data gathering, knowledge sharing, and capacity building.

The development process for EU adaptation framework first led to the adoption of the 2007 Green Paper on adapting to climate change in Europe, recognising that all parts of Europe will increasingly feel the adverse effects of climate change. In 2009 the White Paper “Adapting to climate change: Towards a European framework for action” set out concrete steps to be taken in preparing the 2013 EU strategy on adaptation to climate change2, adopted on 16 April 2013. As stated in the White Paper and further strengthened by the EU Adaptation Strategy, the EU sees its key role to support the public and private sector at national, regional and local levels by providing comprehensive information on adaptation (mainly through the European Climate Adaptation Platform Climate-ADAPT3), by giving directions and advice to ensure coherent adaptation approaches (e.g. through guidelines) and by allocating funding (e.g. through the LIFE programme4) for adaptation action. In addition, the EU has a key role in supporting EU Member States on transboundary issues and further strengthening mainstreaming of adaptation into certain sectors that are closely integrated at EU level through the single market and common policies (EC, 2014). Furthermore, the EU Adaptation Strategy encourages all its Member States to adopt comprehensive adaptation strategies recognising that in particular National Adaptation Strategies (NASs) are widely accepted as key tools to frame consistent action at country level.

As of April 2014, 20 EEA member countries had adopted a National Adaptation Strategy (NAS). Most of the existing strategies include limited information on implementation (e.g. monitoring, financing of adaptation action) and therefore in total 17 countries have set out more detailed national action plans (NAP). Table 1.2 provides an overview of all EEA member countries with NASs/NAPs in place.

Table 1.2. Status National Adaptation Strategies and National Adaptation Plans in European countries (23 May 2014)

[NOTE: Table will be replaced by a graph with updated information]

| EEA Member Country | NAS | NAP |

|---|---|---|

| Austria | 2012 | 2012 |

| Belgium | 2010 | |

| Bulgaria | ||

| Croatia | ||

| Cyprus | ||

| Czech Republic | ||

| Denmark | 2008 | 2012 |

| Estonia | ||

| Finland | 2005 | 2011 |

| France | 2006 | 2011 |

| Germany | 2008 | 2011 |

| Greece | ||

| Hungary | 2008 | Date missing |

| Iceland | ||

| Ireland | 2012 | |

| Italy | ||

| Latvia | ||

| Liechtenstein | ||

| Lithuania | 2012 | Date missing |

| Luxembourg | ||

| Malta | 2012 | 2012 |

| Netherlands | 2008 | |

| Norway | 2013 | 2007 |

| Poland | 2013 | Date missing |

| Portugal | 2010 | Date missing |

| Romania | ||

| Slovakia | 2014 | |

| Slovenia | Date missing | |

| Spain | 2006 | 2014 |

| Sweden | 2009 | Date missing |

| Switzerland | 2012 | 2014 |

| Turkey | 2011 | 2011 |

| UK | 2008 | 2013 |

National Adaptation Strategies and Action Plans provide a general and mostly non-binding policy framework for guiding adaptation activities of governmental authorities and non-state actors. As for other policy domains, policy-making at national level has a key role in creating an enabling environment for planning and implementing concrete actions. It is at this level that medium- to long term adaptation objectives need to be formulated and gain political support as well as that coordination mechanisms are to be established to secure engagement of key actors. Overall, the development of a national adaptation policy (strategy and/or plan) serves as an instrument that provides the necessary frame for adaptation through coordinating the consideration of climate change across relevant sectors, geographical scales and levels of decision-making.

Most national adaptation strategies are being implemented (or will be implemented) by government/interministerial committees or working groups. The objective of these working groups is to create a forum for cross-department working, as well as to reach out to businesses and citizens at the national, regional and local levels. This approach confirms an acceptance of adaptation as something that must be implemented by stakeholders at all levels and in all areas of society, and not something to be pursued in isolation of other policy objectives, programmes and services (EC, 2013). Adaptation is an emerging policy area and it is important for government (national or regional) to facilitate dialogue with the relevant stakeholders and to be leading by example until adaptation becomes firmly embedded. Thus the ambition to mainstreaming adaptation with existing national programmes and policies is central to all NAS. As with mainstreaming adaptation, communication and awareness raising is another key principle that many NAS have in common. Effective communication and raising awareness on climate change adaptation is seen as important factor for successful implementation (McCallum et al., 2013).